paying attention

it was right at the start of quarantine when rachel syme, one of my favorite writers, tweeted offhandedly that she takes a bath every day.

i can't explain it, but that blew my mind. as someone who had luxuriated in the occasional bath, perhaps two or three times a year, i was struck by the revelation that there was nothing stopping me from taking baths anytime i pleased. i, too, could take a bath every single day of my life, if that was what i wanted.

the bathtub became my sanctuary. plumes of steam and smoke and mist, hazy candlelight illuminating shiny white tile, the din of water crashing out of the faucet. a quiet would wash over me, cleansing me, asking nothing and demanding nothing. slowly my thoughts would grow loud and expand to fill the void.

it doesn't feel like a coincidence that this newfound ritual of logging off started in 2020. as devices became our windows to the outside world (even more so than they were before), the urgency around staying online hit a fever pitch. the internet swallowed our relationships, work, school, the news, dating, shopping, entertainment. to me, it started to feel like consuming content was all there was. scroll to be informed, scroll to stay in touch, scroll to stave off boredom. there was content about everything; there was content about how there was too much content.

it became impossible to think and, consequently, to write. the thoughts that did come were so fragmented and disjointed that i might as well have not had them. forming them into a cohesive whole felt like taping a shredded document back together. the inability to think clearly, much less communicate what i was thinking to others, grew agonizing.

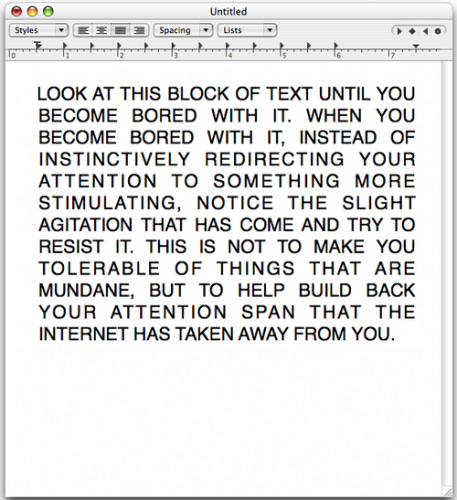

reading books helped. it forced me to process information more slowly and more deeply, to train my attention beyond the length of a tiktok or a tweet. but when chapters inevitably started to drag, i would feel the pull toward my phone, that softly glowing portal to infinite worlds. it would be there, waiting, a sure release from the visceral discomfort of a momentary lack of stimulation. it felt strange to feel that and not immediately quell it by giving it what it wanted. but when the twitchiness passed, i noticed—not always, but sometimes—something beyond it.

and so, late that year, i went even further by working through the artist's way, a self-help book (with some questionably woo-woo ideology but also lots of excellent advice) by julia cameron to help people to recover their creativity. cameron dictates a week of media deprivation as part of the twelve-week program. no reading, no social media, no tv.

the prospect would have been inconceivable just a few months ago. a coworker once told me that i was "the most voracious consumer of media" they'd ever met, a label that didn't feel inaccurate. i had made small attempts at spending less time online, an evening here and a day there, but the benefits of the internet had always been so clear to me that, frankly, it felt silly to forego that by choice even briefly.

but i guess, for the first time, i could see how this kind of exercise might have some value; for the first time, i was realizing that the absence of media wasn't just a loss. it was the regaining of space, free and open space, uncluttered by all the words and images from other people that usually occupied my mind. cameron writes about why we seek out all this noise, calling all the words we read "tiny tranquilizers":

Reading is an addiction. We gobble the words of others rather than digest our own thoughts and feelings, rather than cook up something of our own.

this book was written in 1992, so she wasn't even talking about twitter, just books and newspapers! today, it is a virtue to possess the attention span necessary to read a book—then, books were as much a part of this landscape, the noise of other people's thoughts, as anything else. and yet even then, she touched on this theme that around this time became a meme among self-aware gen z kids, with viral tiktoks and tweets like "i have to consume like 8 forms of media at once to prevent myself from ever having a thought."

this tendency feels most apparent with tiktok. in recent years, a phenomenon has emerged there, what i've called in my head the chaotic duet: an omnibus style of tiktok that pairs unrelated videos together with the duet feature, ostensibly to offer multiple contrasting forms of visual and auditory stimuli at once. the lack of external input—of content to consume—is terrifying to people, to the extent that singular artifacts of media aren't sufficient. you need multiple inputs at once, to hedge against the possibility that one of them will fail to hold your attention and force you to sit in the quiet of your own mind.

perhaps this function of media was obvious to you; perhaps you, like my friend alice, explicitly use it for this purpose. but it wasn't obvious to me. i had convinced myself that i needed to be an engaged citizen, and i needed to interact with people in the tech industry for my career, and i needed to relax and unwind after a long day—that social media and media as a whole served these purposes. which they often do. but i could never isolate just what i needed from the feeds at that moment, leaving aside the rest of it until it was needed, too. it was all or nothing, and who would pick nothing? and, anyway, none of that was sufficient to explain my usage, a screen time that encroached on every waking hour of the day.

richard seymour raises this same point in the twittering machine (which i've quoted in this newsletter in the past), that it's not an unfortunate accident that consuming content absorbs so much of our attention that our own thoughts are suppressed. he proposes that that is what we really want:

What sounds like a problem may be the yield. The opportunity to waste attention, or to dispose of spare attention, may be what we seek.... If we didn’t have somewhere to put excess attention, who knows what dreams would come?

maybe that's the crux of it. bread and circuses, except often now there’s no bread, and we create our own circuses, weary of wanting more for ourselves and each other. easier to crowd out our thoughts and throw away our time than leave room for hopes that can only be disappointed. or maybe that's too pessimistic—but sometimes that feels like where it arises for myself.

either way, i think there is a real drive (whether it's internal or external) toward distraction, even as we want to pay attention. and using social media is undeniably an effort to pay attention; how else would we have built the entire attention economy around it? every post on the feed is vying for a cut—buy this product, like this page, donate to this fund, retweet this joke, spread awareness about this issue. we try in vain to pay out fractional amounts of our attention and find that the whole is, somehow, less than the sum of its parts. in wanting to pay attention to everything, we often fail to pay attention to anything at all.

the costs of that constant state of distraction can be steep. in her quietly radical manifesto disguised as self-help book, how to do nothing, jenny odell writes about how the diminishing capacity to pay attention on an individual level affects us societally:

It’s not just that living in a constant state of distraction is unpleasant, or that a life without willful thought and action is an impoverished one. If it’s true that collective agency both mirrors and relies on the individual capacity to “pay attention,” then in a time that demands action, distraction appears to be (at the level of the collective) a life-and-death matter. A social body that can’t concentrate or communicate with itself is like a person who can’t think and act.

if it feels like i'm rehashing earlier writings, i am—a big question that's plagued me for years now is, what do we do with all this conflicting information, all seemingly dire and immediate? it can feel like a civic responsibility to be aware of everything happening everywhere, but maybe it's worth calling into question the value of that heightened awareness, especially if we find that it makes it harder for us to act on it. faced with a hundred pressing issues all demanding our attention, we start to lose our sense of perspective, along with the sustained focus that changemaking requires.

and while i've talked a lot about space, the dimension that interacts most with attention is time. i spend a lot of time thinking about time—how we conceptualize it, how we experience it, how it expands and contracts beneath different lenses. focus is about the ability to direct attention for a duration of time. boredom is about the discomfort that comes from a perceived slowness of time. having less mental space might be the outcome of consuming all this content, but wanting less time is the more explicit reason we do it. that was the most disorienting part of our media deprivation week—i'm so used to thinking i'm busy, that i don't have enough time to do everything i say i want to do, but after i stopped consuming so much, i realized that that was entirely untrue. i have so much time. and having all that time is deeply uncomfortable for me, so i find ways to "spend" it or "pass" it, like it's some kind of irritatingly infinite waste product of which i can't wait to be rid. i have to actively remind myself that that is not, in fact, true.

oliver burkeman wrote in his thought-provoking book on this subject, four thousand weeks, about the historical shift in people's relationship with time:

Before, time was just the medium in which life unfolded, the stuff that life was made of. Afterward, once “time” and “life” had been separated in most people’s minds, time became a thing that you used—and it’s this shift that serves as the precondition for all the uniquely modern ways in which we struggle with time today. Once time is a resource to be used, you start to feel pressure, whether from external forces or from yourself, to use it well, and to berate yourself when you feel you’ve wasted it.

i can recall specific points in my life when time just felt like existence. every summer before college. meandering days with friends that unwinded in unexpectedly fruitful ways purely by chance. burning man. the few vacations that were able to pull me into a different timestream. but they are rare, much rarer than i ever would have thought they'd be. more often, time feels like a resource to be divvied up into usable pieces. an hour or two to read, half an hour to run an errand, an hour to cook, fifteen minutes to eat, a few hours to work for money, a few hours to work toward some kind of fulfillment outside of work, several hours for sleep. i'm constantly budgeting my time, and i'm constantly conscious of its passage, vacillating between fear of its disappearance and fear of its abundance. in either instance, i'm hyperaware of its separateness from the experience of existing.

the addiction metaphor for social media is, at this point, so terribly overwrought that it feels banal to mention it, but this line from the twittering machine has rattled around my brain nonstop since i read it:

Schüll calls it the ‘machine zone’ where ordinary reality is ‘suspended in the mechanical rhythm of a repeating process’. For many addicts, the idea of facing the normal flow of time is unbearably depressing. Marc Lewis describes how even after kicking junk he couldn’t face ‘a day without a change of state’.

i realized at some point that i don't like baths or massages or workouts just because they feel good, physically (although they do). i like them because they're time without my phone, time to properly and intentionally inhabit my body, time to experience time. i spend so much of my life immersed in information, carried by it like river rapids, that it's a novelty to be brought back, if only for an hour, to a passage of time measurable by breaths.

one excerpt from "the new year train" by the chinese sci-fi writer hao jingfang (translated by ken liu in broken stars) has stayed with me:

Li: ...if the starting point and the destination are already set, and if no matter how many days it takes to get there, you’ll arrive on time, then wouldn’t you want to prolong the trip as much as possible to enjoy it?

Reporter: I guess so. It’s like free time.

Li: It’s simple when you put it like that, right? What doesn’t make sense to me is this: lots of times, when the starting point and the destination are fixed—say, birth and death—why do most people rush toward the end?

i've often wondered what it means for so many of us to be living life in hyperreality, at hyperspeed. if we think of media as a kind of time travel, a fast-forward button for life, what's the point of it all? where are we rushing to go? life isn't somewhere else, ahead of us on the horizon. we're already here.

snippets

i wrote the start of this post all the way back in 2020, which feels like an eternity ago now. i picked it up again briefly in 2021, but it was such a large topic, and one that i wanted to articulate sufficiently, that i grew discouraged and left it in the drafts. perfectionism: it’s a plague! one problem was that i had collected too many quotes and excerpts that i wanted to weave into the post and couldn’t find good spots for them, so here they are anyway.

first, on time—mary retta once wrote about her experience of time, in one of the most poetic and striking pieces i've ever read on the subject, "on vibing":

This notion of time as an “economic resource” is exactly what vibing aims to break away from. It is not a coincidence that the last year has brought both the collapse of capitalism and an upending of time. This year of stillness and retreat has made it plain that time is not an empty thing we have to fill but a living thing that we must shape. Time changes. Because the world changes, and we change with it. To vibe is to shape time into pleasure, to mold it into something that feels soft and tastes sweet. It is to take a pause that bleeds into another. “Until finally,” writes Githere, “the space between the dream and the memory collapses into being your reality—now.”

bonnie tsui had a lovely opinion piece in the new york times called "you are doing something important when you aren't doing anything," an argument for what she calls "fallow time":

Protecting and practicing fallow time is an act of resistance; it can make us feel out of step with what the prevailing culture tells us. The 24/7 hamster wheel of work, the constant accessibility and the impatient press of social media all hasten the anxiety over someone else’s judgment. If you aren’t visibly producing, you aren’t worthy. In this context, taking time to lie dormant feels greedy, even wasteful.

in the new republic, "in the defense of nothing" by apoorva tadepalli reclaimed the idea of the slacker, embracing idleness:

The slacker embodies their own powerful virtue: that of “unreal hopes, ill-considered plans,” of wanting “the whole world or nothing,” as Chinaski declares. The slacker loves the world as it is and not simply as it’s best presented. In our mad rush for empty busywork that can be dressed as productivity, we seem to prefer the world in its “perfect” state, as Taylor points out. It seems, then, that we do not love the world at all.

and then, related to consumption and media as a response to this dilemma of time—i'm currently reading neal gabler's life: the movie, on the rise of entertainment as an industry and how it came to subsume all other facets of life, too:

Art was said to provide ekstasis, which in Greek means “letting us stand outside ourselves,” presumably to lend us perspective. But everyone knows from personal experience that entertainment usually provides just the opposite: inter tenere, pulling us into ourselves to deny us perspective.

designer aaron lewis wrote "inside the digital sensorium", another longtime favorite:

Every day, thousands of strangers upload little slices of their consciousness directly into my mind. My concern is that I'm prone to mistake their thoughts for my own — that some part of me believes I'm only hearing myself think. Sometimes when I wake up in the morning, I'll scroll through my old posts just to remind myself of myself. It feels like looking in the mirror. I'm swallowing my (digital) self so that I'm me instead of someone else.

kyle chayka wrote about the culture of negation that's emerged out of the specifically modern need to cope with reality by paring back in "how nothingness became everything we wanted":

This obsession with absence, the intentional erasure of self and surroundings, is the apotheosis of what I’ve come to think of as a culture of negation: a body of cultural output, from material goods to entertainment franchises to lifestyle fads, that evinces a desire to reject the overstimulation that defines contemporary existence.

and, finally, the postscript on each newsletter from product lost by reggie james has always stuck in my mind:

Thanks so much for giving me your attention. I hope it was worth it, if not… unsubscribing will not hurt my feelings, and will give you back time you literally cannot have back.

the dream machine is designed to be read with music, but the fifteen-second clips that play with the spotify embeds have never been quite what i envisioned for the experience, so i finally made a proper playlist. here’s the soundtrack if you’d like to listen as you read!

as always, responses are my single favorite part about sharing to this newsletter, so if anything sparks a thought for you, i would love to hear it.